- Home

- Troy Denning

The Parched Sea Page 4

The Parched Sea Read online

Page 4

The youth sneered doubtfully and declared, “That cannot be.” He studied her for a moment with accusatory eyes, then demanded, “If everybody else is dead, how did you survive?”

Ruha pushed herself from beneath the camel. “What do you suggest?” she snapped, standing. “Do you insult the woman whom you are duty-bound to honor?”

Cowed by her sharp tone, the boy retreated two full steps, shaking his head. At the same time, the camels echoed Ruha’s indignation and roared with impatience. They could no doubt smell the oasis and were anxious to quench their thirst in its pool.

Remembering the one-eyed man and his two guides, Ruha quickly turned to calm the camels. Until now, she had not worried about being overheard by the three strangers, for she and Kadumi were far enough away from the oasis that their voices would be muffled by sand dunes. A camel’s bellow was a different matter. A roar like the ones the creatures had just voiced could be heard miles away.

“We’ve got to keep the camels quiet,” she said, urgently grabbing the nose of the nearest one. “There are three strangers in the oasis.”

Kadumi did not move to help her. “Just three?” he scoffed, stepping toward his brown riding camel. “I have my bow and plenty of arrows. They shall pay the blood price.”

Ruha moved to the boy’s side and caught his arm. “No,” she said. “They weren’t with the fork-tongues.” She told him about how the one-eyed stranger had appeared in the caravan’s wake last night, then of spending the morning watching the man and his short companions in camp.

“It does not matter whether their hands bear the blood of battle or the blood of desecration,” Kadumi insisted. “They deserve to die.” He pulled his arm free of her grasp.

From his stubborn tone, Ruha realized that the boy was looking not so much for vengeance as an excuse to vent his anger. Unfortunately, remembering the sharp instincts of the one-eyed man, Ruha knew that allowing Kadumi to attack would mean his death. As the youth reached for his arrow quiver, the widow slipped between him and his camel. “They are three and you are one.”

Kadumi side-stepped her and snatched his quiver off the saddle.

Wondering if her husband had been as stubborn and foolish in his youth, Ruha grasped the boy by both shoulders. “It is foolish to attack,” she said. “Even Ajaman would not have tried such a thing.”

Kadumi ignored her and tried to pull free. When she did not release him, he drew his jambiya. The boy’s anger took Ruha by surprise, and she found the curve of his knife blade pressed against her throat.

His lower lip quivering in anger, Kadumi yelled, “Ajaman is not here!”

“But you are, and you are dishonoring your brother by threatening his wife,” Ruha countered. “You must protect your brother’s widow for two years. If you get killed, who will take care of me?”

Tears of despair welled in the boy’s eyes. After a moment of self-conscious consideration, he rubbed the tears away and sheathed his jambiya. He turned from her and stared at his camels for several minutes. Finally he said, “I will take you to your father and return to kill the defilers later. Anyway, from what you have said, it appears that the fork-tongues are moving toward the Mtair Dhafir’s oasis, so we should try to warn them.” The youth looked westward. “I have extra camels, and they are all strong. We can ride hard, and perhaps we will reach the Mtair Dhafir ahead of the fork-tongues.”

The widow shook her head. “I’ve made certain promises to Ajaman. We must wait here until we can take his body to the oasis,” she said. “Then we can warn the Mtair Dhafir.”

Ruha was not anxious to return to her father’s tribe, but Kadumi was right to alert them to the danger traveling in their direction. Besides, even though she knew it would be impossible for her to stay with the Mtair Dhafir, there was no reason for them to turn out the young warrior, and the widow suspected that it would be easier to find a new tribe for herself if she left her young brother-in-law with the Mtair.

Accepting Ruha’s plan with a respectful nod, Kadumi cast a wary eye toward the southern sky. “Let us hope the strangers leave soon,” he said. “If that storm catches us in its path, we will have to wait it out.”

Three

From beneath a fallen tent, Lander heard his guides approaching. Pitched on the southern end of the oasis pond, about a hundred feet from the camp, this tent was the first in which he had found no bodies. It was also a stark contrast to the clutter of the other tents, for there was nothing inside except a ground-loom, three cooking pots, a dozen shoulder bags of woven camel hair, and a few other household items. Apparently the inhabitants of this household had escaped the massacre. Lander wondered how.

“Lord, there are camels out in the sands!” called Bhadla, the elder of his two guides.

“I’m not a lord,” Lander responded wearily, correcting the solicitous servant for the thousandth time. He found a twelve-inch tube made of a dried lizard skin and sniffed the greasy substance inside. It was foul-smelling butter.

“Whatever it is you wish to be called,” Bhadla said, “I hope you have finished whatever you are doing with those dead people. We must go.”

“Go?” Lander asked, crawling toward the voice. “What for?”

Like his guides, he had heard the camels roaring outside the oasis, but he had no intention of leaving. He had come to this wretched desert to find the Bedine, not flee from them.

Lander reached the edge of the tent and pushed his head and shoulders out from beneath it. The blazing sunlight reflected off the golden sands and stabbed painfully at his one good eye. “What’s this about going?”

“Someone is coming,” the short guide repeated. “We shouldn’t be here when they arrive.”

“They’ll think we did this,” offered Musalim, Bhadla’s scrawny assistant.

Like all D’tarig, Bhadla and Musalim stood barely four feet tall. Each kept himself swaddled in a white burnoose and turban from head to foot. Lander wondered what they looked like beneath their cloaks and masks, but knew he would probably never find out. He had met dozens of the diminutive humanoids over the last few months, and he had yet to glimpse anything more than a leathery brow set over a pair of dark eyes and a black, puggish nose.

“I doubt anyone will think the three of us murdered an entire tribe,” Lander said.

“The Bedine might,” Bhadla said. He brushed the back of his fingers against his forehead in a disparaging gesture Lander did not understand. “They have very bad tempers.”

“When I hired you, you assured me you were very popular with the people of the desert,” Lander said, crawling the rest of the way from beneath the tent.

As he stood, he noticed that a gray haze was spreading northward from the southern horizon. In Sembia, his home, such a cloud signaled the approach of a storm. He hoped it meant the same thing in the desert, for a little rain might break the oppressive heat.

Turning his attention back to his guide, he said, “Are you telling me you lied, Bhadla?”

Bhadla shrugged and looked away. “No one can say what the Bedine will do.”

“I can,” Lander countered.

Musalim scoffed. “How could you? Bhadla cannot even tell which tribe this—”

Bhadla cuffed his assistant for this indiscrete admission. In the language of his people, the D’tarig said, “Watch your tongue, fool!”

Though he wore a magical amulet that allowed him to comprehend and speak D’tarig, Lander feigned ignorance. Since both of his guides spoke Common, the universal trade language of Toril, he had seen no reason to let them know he could understand their private conversations.

“I do not need to know the name of this tribe to know they will kill those who loot their dead,” Lander said, looking pointedly from one D’tarig to the other.

The hands of both guides unconsciously brushed the pockets hidden deep within their burnooses. “What do you mean, Lord?” Musalim asked suspiciously.

Lander smiled grimly. “Nothing, of course,” he replied. “But if I ha

d taken anything off the bodies of the dead—rings off their fingers or jewels from their scabbards, for example—I would also be anxious to leave.”

Musalim furrowed his barely visible brow, but Bhadla seemed unimpressed. “Bah!” the older D’tarig said. “The survivors will think the raiders took these things.”

Lander looked toward the sand dunes. “I don’t think so,” he said. The figure that had been watching them all morning was gone—but not far, he suspected. “They’ve seen with their own eyes who looted the dead.”

Musalim’s eyes opened wide. “No, Lord!”

“I’m no lord,” Lander snapped. “Don’t address me as if I were.”

Bhadla’s eyes narrowed. “You’re lying.”

“Not at all,” Lander replied. “My father was a wealthy but untitled merchant of Archenbridge, and my mother was … well, there’s no need to discuss her. Let’s just say I’m no lord.”

Bhadla shook his turbaned head angrily. “I don’t care if your mother was a goat who gave milk of silver and urine of gold!” he yelled. “Were the Bedine watching or not?”

Lander flashed a conciliatory smile. “I never lie.”

The D’tarig uttered a curse in his own throaty language, then began pulling jewels and rings out of his pockets. Laying the booty on the camel-wool tent at Lander’s side, he hissed, “You should have told us!”

“You shouldn’t have taken it,” Lander replied.

“It’s not our fault,” Musalim complained, also emptying his pockets. “Those who attack should take the plunder, not leave it to tempt us. Who razes an entire camp and steals nothing but camels?”

Studying the devastated oasis with a grim expression, Lander answered, “The Zhentarim.”

“Black Robes?” Bhadla echoed. “They couldn’t have done this. They’re just traders.”

Lander could understand Bhadla’s misconception. The D’tarig lived on the fringes of Anauroch. They survived by goat herding, but the most adventurous and greedy ventured into the Great Desert. These “desert walkers” collected resin from cassia, myrrh, and frankincense trees, then sold it to merchants sponsored by Zhentil Keep. The Zhentarim resold it to temples all over the realms for use as incense. As far as the D’tarig knew, the Black Robes were nothing more than good merchants.

“The Zhentarim are much more than traders,” Lander explained, turning to face Bhadla. “They’re an evil network of thieves, slave-takers, and murderers motivated by power, lust, and greed. They rule hundreds of towns and villages, control the governments of a dozen cities, and have placed spies in the elite circle of practically every nation in Faerun.”

Musalim shrugged. “So?”

“The Zhentarim want to monopolize trade and control politics over all of Faerun,” Lander said. “They want to make slaves of an entire continent.”

Dumping his last ring onto the collapsed tent, Bhadla said doubtfully, “I don’t believe that. Wealth is one thing, but who would want the trouble of so many slaves?”

The Sembian shook his head. “I don’t know why the Zhentarim want what they want, Bhadla,” he said. “Maybe they’re working on Cyric’s behalf.”

“What is this Cyric?” interrupted Musalim, still searching the hidden pockets of his robe.

“He was once a man, but now he’s a god—the god of death, murder, and tyranny,” Lander answered.

“In the desert, he is called N’asr,” Bhadla explained.

Musalim nodded thoughtfully, as if the god’s involvement explained everything.

“The Bedine claim N’asr is the sun’s lover,” Bhadla continued. “The sun, At’ar, forsakes her lawful husband every night to sleep in N’asr’s tent.”

Lander ran his fingers over the blisters on his sunburned face. “I don’t doubt it,” he said, squinting up at the sky. “She certainly seems brutal enough to be Cyric’s lover.”

“Perhaps N’asr, er, Cyric has sent the Zhentarim into the desert to kill At’ar’s husband,” Musalim suggested. “Jealously has caused many murders.”

Lander chuckled. “I don’t think so, Musalim. In this case, I think they’re after gold.”

“Gold?” Bhadla queried, perking up. “There’s none of that in Anauroch, is there?”

“They’re not looking for gold in the desert,” Lander explained. “They’re going to carry it across the desert.” He pointed westward. “Over there, two thousand miles beyond the horizon, lies Waterdeep, one of many cities of great riches.” Next, he pointed eastward. “Over there, five hundred miles from the edge of the desert, are Zhentil Keep, Mulmaster, and the other ports of the Moonsea. They serve as the gateways to the ancient nations of the Heartlands and to the slave-hungry lands of the South.”

The two D’tarig frowned skeptically, and Lander guessed that the desert-walkers were having trouble imagining a world of such scope. “In the center of all these cities are six-hundred miles of parched, burning sands that fewer than a dozen civilized men have ever crossed.”

Musalim picked up a handful of sand and let it slip through his fingers. “You mean these sands?”

“Yes,” Lander confirmed. “And whoever forges a trail through this desert controls the trade routes linking the eastern and western sides of Faerun.”

“There you are mistaken,” Bhadla said, his eyes sparkling with faintly kindled avarice. “The land surrounding the desert belongs to the D’tarig, so we will control this trade.”

“If you think the Zhentarim will honor your territorial rights, you are the one who is mistaken,” Lander said. “When the time comes, they will find a way to steal your land.”

“You underestimate us, Lord,” Bhadla said. “The Zhentarim may have cheated many in your land, but they cannot beguile the D’tarig.” As if he had said all that needed to be said on the matter, the guide turned to Musalim. In D’tarig, he asked, “Have you returned all you took from the Bedine?”

“Yes,” Musalim answered, a note of melancholy in his voice.

Bhadla turned back to Lander, then took the Sembian’s arm and tugged him toward their camels. “Come, it is time for us to ride.”

Lander refused to budge. “I’m waiting for the Bedine.”

“If they have not come by now, they are not going to,” Musalim said. “They are a shy people, and the survivors of what happened here are certain to be more so.”

“There are two more oases within two days’ ride,” Bhadla added. “Perhaps another tribe will be camped at one of them.”

Lander’s stomach tightened in alarm. “Where are these oases?”

Bhadla pointed in the direction the Zhentarim had taken after destroying the camp last night.

Without speaking a word, Lander started toward the oasis pond, where the camels were tethered. Previously he had been puzzled by the Zhentarim’s quick departure last night. Now he realized they were trying to reach the next tribe before it learned of the slaughter at this oasis.

When Bhadla and Musalim caught up to him, Lander glared at the guides. “Why didn’t you tell me about the other oases earlier?”

Bhadla shrugged. “I would have, if you had told me we were being watched.”

Irritated by the D’tarig’s reply, Lander quickened his pace. “Don’t fill more than three waterskins,” he snapped. “We’ll have to ride hard to beat the Zhentarim to the next oasis, and the extra weight will only slow us down.”

Musalim pointed at the haze on the southern horizon. “But, Lord, we may need a lot of water. That storm could force us to stop for several days!”

“We’re not going to stop because of a little rain.”

Bhadla snickered. “Rain? In Anauroch?”

“That’s a sandstorm!” added Musalim.

The trio reached the camels a moment later, and the beasts lowered their heads to the water for one last drink. Lander undid the tethers of his mount, then paused to look southward. The haze was creeping steadily forward, streaking the sapphire sky with gray, fingerlike tendrils.

“I don’t

care if it’s a firestorm,” the Sembian said. “It’s not going to stop us.”

In the end, the D’tarig insisted upon filling six waterskins, but at Lander’s direction, they agreed to push their camels along at a trot. The trio covered more than a dozen miles by early afternoon, and the sands paled to the color of bleached bones. The dunes changed orientation so that they ran east-west and towered as high as five hundred feet. Lander was glad their path ran parallel to the great dunes rather than across them. The Sembian felt sure that scaling one of the steep, shifting slopes would have been as hard on the camels as trotting for an entire day.

The dunes’ great size did not make them any less barren. The only sign of vegetation was an occasional parched bush that had been reduced to a bundle of sticks by an untold number of drought years. Even the camels, which usually tried to eat every stray plant they happened upon, showed no interest in the desiccated shrubs.

The storm crept closer, obscuring the sky with a haze that did nothing to lessen the day’s heat. The blistering wind, blowing harder with each passing hour, felt as though it had been born in a swordsmith’s forge. On its breath, it carried a fine silt that coated the trio’s robes with gray dust and filled Lander’s mouth with a gritty thirst that he found unbearable. Soon he was glad his guides had insisted upon filling extra skins, for he found himself sipping water nearly constantly.

Bhadla slowed his camel and guided it to Lander’s side, leaving Musalim fifty yards ahead in the lead position. The D’tarig always insisted upon riding a short distance ahead to scout. Lander did not argue, for it spared him their constant, inane chatter.

“This is going to be a very bad storm, Lord,” Bhadla said. “I fear that, when it grows dark, we will have to stop or lose our way. There will be no stars to guide us.”

“Don’t worry. I will always know which direction we are traveling.” He purposely did not tell his guide about the compass he carried, for he suspected the D’tarig would steal such a useful device at the first opportunity.

Bhadla shook his head at his employer’s stubbornness. “It may not be as important to beat the Zhentarim to the next oasis as you think,” he said. “Bedine scouts range far. They probably know of the Black Robes already.”

Shadows of Reach: A Master Chief Story

Shadows of Reach: A Master Chief Story Pages of Pain p-1

Pages of Pain p-1 Star Wars 396 - The Dark Nest Trilogy III - The Swarm War

Star Wars 396 - The Dark Nest Trilogy III - The Swarm War Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Apocalypse

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Apocalypse A Forest Apart

A Forest Apart Star Wars: Dark Nest II: The Unseen Queen

Star Wars: Dark Nest II: The Unseen Queen Star Wars: A Forest Apart

Star Wars: A Forest Apart Tempest: Star Wars (Legacy of the Force) (Star Wars: Legacy of the Force)

Tempest: Star Wars (Legacy of the Force) (Star Wars: Legacy of the Force) Star by Star

Star by Star Crucible: Star Wars

Crucible: Star Wars Last Light

Last Light Invincible

Invincible Inferno

Inferno Star Wars - The Trouble With Squibs

Star Wars - The Trouble With Squibs Abyss

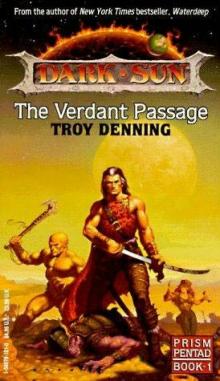

Abyss The Verdent Passage

The Verdent Passage Vortex: Star Wars (Fate of the Jedi) (Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi)

Vortex: Star Wars (Fate of the Jedi) (Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi) Dragonwall e-2

Dragonwall e-2 The Amber Enchantress

The Amber Enchantress Crucible

Crucible The Titan of Twilight

The Titan of Twilight Dragonwall

Dragonwall Beyond the High Road c-2

Beyond the High Road c-2 The Siege rota-2

The Siege rota-2 Silent Storm: A Master Chief Story

Silent Storm: A Master Chief Story The Ogre's Pact

The Ogre's Pact The Sorcerer rota-3

The Sorcerer rota-3 The Parched sea h-1

The Parched sea h-1 The Giant Among Us

The Giant Among Us Recovery

Recovery Star Wars: Dark Nest 1: The Joiner King

Star Wars: Dark Nest 1: The Joiner King Faces of Deception le-2

Faces of Deception le-2 The Parched Sea

The Parched Sea The Ogre's Pact зк-1

The Ogre's Pact зк-1 Apocalypse

Apocalypse Star Wars®: Dark Nest I: The Joiner King

Star Wars®: Dark Nest I: The Joiner King The Titan of Twilight ttg-3

The Titan of Twilight ttg-3 The Giant Among Us ttg-2

The Giant Among Us ttg-2 The Summoning rota-1

The Summoning rota-1 Tatooine Ghost

Tatooine Ghost Star Wars®: Dark Nest III: The Swarm War

Star Wars®: Dark Nest III: The Swarm War Retribution

Retribution A Forest Apart: Star Wars (Short Story)

A Forest Apart: Star Wars (Short Story) Faces of Deception

Faces of Deception The Veiled Dragon h-12

The Veiled Dragon h-12 Star Wars 390 - The Dark Nest Trilogy I - The Joiner King

Star Wars 390 - The Dark Nest Trilogy I - The Joiner King Waterdeep

Waterdeep STAR WARS: NEW JEDI ORDER: RECOVERY

STAR WARS: NEW JEDI ORDER: RECOVERY