- Home

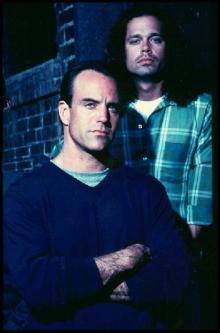

- Troy Denning

Dragonwall e-2

Dragonwall e-2 Read online

Dragonwall

( Empires - 2 )

Troy Denning

Troy Denning

Dragonwall

1

The Minister's Plan

The barbarian stood in his stirrups, nocking an arrow in his horn-and-wood bow. He was husky, with bandy legs well suited to clenching the sides of his horse. For armor, he wore only a greasy hauberk and a conical skullcap trimmed with matted fur. His dark, slitlike eyes sat over broad cheekbones. At the bottom of a flat nose, the rider's black mustache drooped over a frown that was both hungry and brutal. He breathed in shallow hisses timed to match the drumming of his mount's hooves.

As he studied the horsewarrior's visage, a sense of eagerness came over General Batu Min Ho. The general stood in his superior's roomy pavilion, over a mile away from the rider. Along with his commander, a sorcerer, and two of his peers, Batu was studying the enemy in a magic scrying basin. Physically, the barbarian looked no different from the thieving marauders who sporadically raided the general's home province, Chukei. Yet, there was a certain brutal discipline that branded the man a true soldier. At last, after twenty years of chasing down bands of nomad raiders, Batu knew he was about to fight a real war.

Batu forced himself to ignore his growing exhilaration and concentrate on the task at hand. Staring into the scrying basin, he felt as though he were looking into a mirror. Aside from the barbarian's heavy-boned stature and coarse mustache, the general and the rider might have been brothers. Like the horseman, Batu had dark eyes set wide over broad cheeks, a flat nose with flaring nostrils, and a powerful build. The pair was even dressed similarly, save that the general's chia, a long coat of rhinoceros-hide armor, was nowhere near as filthy as the rider's hauberk.

"So, our enemies are not blood-drinking devils, as the peasants would have us believe." The speaker was Kwan Chan Sen, Shou Lung's Minister of War, Third-Degree General, and Batu's immediate commander. An ancient man with skin as shriveled as a raisin's, Kwan wore his long white hair gathered into a warrior's topknot. A thin blue film dulled his black eyes, though the haze seemed to cause him no trouble seeing.

By personally taking the field against the barbarians, the old man had astonished his subordinates, including Batu. Kwan was rumored to be one hundred years old, and he looked every bit of his age. Nevertheless, he seemed remarkably robust and showed no sign of fatigue from the hardships of the trail.

Resting his milky eyes on Batu's face, the minister continued. "If we may judge by the enemy's semblance to General Batu, they are nothing but mortal men."

Batu frowned, uncertain as to whether the comment was a slight to his heritage or just an observation. An instant later, he decided the minister's intent did not matter.

Settling back into his chair, Kwan waved a liver-spotted hand at the basin. "We've seen enough of these thieves," he said, addressing his wu jen, the arrogant sorcerer who had not even bothered to introduce himself to Batu or the others. "Take it away."

As the wu jen reached for the bowl, Batu held out his hand. "Not yet, if it pleases the minister," he said, politely bowing to Kwan.

Batu's fellow commanders gave him a sidelong glance. He knew the other men only by the armies they commanded-Shengti and Ching Tung-but they made it clear that they felt it was not Batu's place to object. They were both first-degree generals, each commanding a full provincial army of ten thousand men. In addition, both Shengti and Ching Tung were close to sixty years old.

On the other hand, Batu was only thirty-eight, and, though he was also a first-degree general, he commanded an army of only five thousand men. In the hierarchy of first-degree generals, the young commander from Chukei clearly occupied the lowest station.

Nevertheless, Batu continued, "If it pleases Minister Kwan, we might benefit from seeing the skirmish line again."

Kwan twisted his wrinkles into a frown and glared at his subordinate. Finally, he pushed himself out of his chair and said, "As you wish, General."

Batu was well aware of the minister's displeasure, but he was determined not to allow an old man's peevishness to drive him into the fight prematurely. The surest way to turn a promising battle into an ignominious defeat was to move into combat poorly prepared.

The wu jen circled his bejeweled hand over the basin, muttering a few syllables in the mysterious language of sorcerers. As the barbarian's face faded, a field covered with green-and-yellow sorghum appeared. Along its southern edge, the field was bordered by a long, barren hillock. A small river, its banks covered with tall stands of reeds, bordered the northeastern and eastern edges. Swollen with the spring runoff from far-away mountains, the river was brown and swift.

The only visible Shou troops were Batu's thousand archers, who had formed a line stretching from the river to the opposite side of the field. Each man stood behind a chest-high shield and wore a lun'kia, a corselet that guarded his chest and stomach. Made of fifteen layers of paper and glue, the lun'kia was inexpensive and remarkably tough armor. The archers' heads were protected by chous, plain leather helmets with protective aprons that covered both the front and back of the neck.

Even through the scrying basin, Batu could hear the tension in his officers' voices as they shouted the command to nock arrows. The archers were unaccustomed to being left exposed, for in previous engagements the general had always supported them with infantry and his small contingent of cavalry. This time, the rest of Batu's army was hiding behind the hill, along with twenty thousand men from the armies of the other two provincial generals. These reinforcements were ready to charge over the hill at a moment's notice.

The archers were bait, and they knew it. If the battle proceeded according to Minister Kwan's plan, the barbarian cavalry would sweep down on them. As the horsewarriors massacred the archers, the twenty-four thousand reinforcements would rush over the hill and wipe out the invaders in one swift blow. The plan might have been a good one, had the horsemen been the unsophisticated savages Kwan imagined.

But the enemy showed no sign of taking the bait. So far, all they had done was ride forward and shoot a few arrows. When the archers returned fire, they always turned and fled.

As Batu and the others watched, a subdued and distant thunder rolled out of the scrying basin. A moment later, two thousand horsemen rode into view on the northern edge of the field, five hundred yards from the archers. At first, the dark line advanced at a canter. Then, at some unseen signal, all two thousand men urged their mounts into a full gallop.

The minister and the generals leaned closer to the scrying basin, watching intently. Two hundred and fifty yards out, the barbarians began shooting. Few of the shafts found their marks, for firing from a moving horse was difficult and the range was great. Still, Batu found it disturbing that any of his men fell, for he did not know a single Shou horseman who could boast of hitting such a distant target from a galloping mount.

Although they were equipped with five-foot t'ai po bows that could match the barbarians' range, Batu's archers held their fire. They had been trained not to waste arrows on unlikely shots and would not loose their bamboo shafts until the enemy had closed to one hundred yards. The horsemen continued to advance, pouring arrows at the Shou line in a haphazard fashion that, nevertheless, dropped more than a dozen of Batu's men.

Finally, the horsewarriors came into range. The Shou fired, and a gray blur obscured the scene. A thousand arrows sailed over the sorghum, finding their marks in the barbarian line. Riders tumbled from their saddles. Wounded horses stumbled, then crashed end-over-end as momentum carried them forward after their legs had gone limp.

Through the scrying basin, Batu heard the screams of dying men and the terrified shrieks of wounded horses. It was not a sound he enjoyed, but neither did it trouble him. He was a gene

ral, and generals could not allow themselves to be distressed by the sounds of death.

The Shou archers fired again. Another gray blur flashed across the field, then more shocked yells and frightened whinnies drifted out of the basin.

"Look!" said Shengti. "They're not breaking off!"

He was right. The barbarians had ridden through two volleys of arrows and were continuing their charge. Batu's stomach knotted just as if he were standing with his men.

"Shall we attack?" asked Ching Tung. He had already turned away from the scrying basin and was moving toward the door.

Noting that none of the riders were drawing their swords or lances, Batu grasped Ching Tung's shoulder. "No!"

As Ching Tung turned to face him, Batu continued, "They're only testing our formation's discipline. If they had intended to finish the charge, they would have drawn their melee weapons by now."

Ching Tung's eyes flashed. He started to say something spiteful, but the thunder in the scrying basin suddenly died. The resulting quiet drew all eyes back to the pool. The generals saw that the enemy horsemen had reigned their mounts to a halt at fifty yards. Batu would have given ten thousand silver coins to know how many more barbarians lurked out of the scrying basin's view. It was a question he knew would not be answered. Kwan's wu jen had already explained that his spell had a range of only two miles.

Another gray blur flashed over the field as the barbarian riders fired in unison. The Shou archers, who had been drawing swords and preparing to meet the charge, were not prepared for the attack. Dozens of arrows struck their marks with quiet thuds. Over a hundred men cried out and fell to the flurry.

Batu's troops were well disciplined, however, and a volley of Shou arrows answered a moment later. Another wave of terrible screams and whinnies followed, and the general from Chukei could almost smell the odor of fresh blood.

For several minutes, gray clouds of arrows flew back and forth as the two lines traded volleys. At such close range, arrows penetrated armor as easily as silk. Hundreds of Batu's men fell. Some remained silent and motionless, but most writhed about, screaming in pain and grasping at the feathered shafts lodged in their bodies.

After every volley, a few Shou survivors threw down their weapons and turned to flee. Without exception, they were met by officers who cut them down with taos, single-edged, square-tipped swords. Batu disliked seeing his officers dispatch his own men, but he detested watching soldiers under his command turn coward and flee. As far as he was concerned, those who dishonored him by running deserved to perish at the hands of their own officers.

Another Shou volley struck the barbarian line. Hundreds of men fell from their saddles or leaped away as their wounded horses dropped thrashing to the ground. Batu noticed that behind the enemy line, no officers waited to cut down cowards. There was no need. Despite the heavy casualties, not a single barbarian panicked or fled.

"The barbarians outnumber our archers two-to-one," observed Shengti. "Why don't they finish their charge?"

"Because they are unsophisticated savages who have never faced soldiers as disciplined as those in the Army of Chukei. They are frightened," Minister Kwan responded, gracing Batu with a commending smile.

Despite the compliment, the old man's rationalization alarmed Batu. If Kwan could not see that the enemy was as well disciplined as any Shou army, he was not fit for his position.

"Minister Kwan," Batu asked, "was the Army of Mai Yuan not disciplined?" He inclined his head slightly, trying to make his point seem a genuine question.

"The enemy took Mai Yuan by surprise," Kwan responded, an edge of irritation in his voice. "General Sung could not have known they would breach the Dragonwall."

"If I may," Batu responded, taking pains to keep his face relaxed and to conceal his growing vexation, "I would suggest that if the barbarians surprised Mai Yuan, they can also surprise us. It would be a mistake to underestimate their sophistication or their bravery."

The wrinkles on Kwan's brow gathered into an angry gnarl, and he glared at Batu with his cloudy eyes. "I can assure the young general that I would make no such mistake."

As Kwan spoke, the enemy cavalry wheeled about and rode for the far side of the field. When his officers showed the proper restraint and did not pursue, Batu breathed a sigh of relief. From the behavior of the barbarians, the young general suspected the horsewarriors were trying to lure his men into a trap.

More than three quarters of Batu's archers, over seven hundred and fifty, lay wounded or dead. As military protocol dictated, every third survivor tended to the injured, dragging those who could not walk away from the battle line. The other survivors stood ready, prepared in case the enemy suddenly returned. The number of casualties unsettled Batu, for the heavy losses reflected too well on the accuracy of the enemy bowmen. Nevertheless, he was also proud of his troops' bravery and discipline.

As the barbarian cavalry rode out of the scrying basin's range, Kwan pointed a wrinkled fingertip at the bowl. "Do you see, General Batu?" he asked. "There is no need to worry about the barbarians. They are frightened of your archers, and with good reason." The old man pointed to where the enemy horsewarriors had stopped and traded arrows with the Shou archers.

What Batu saw disappointed him. Dozens of injured barbarians were limping or crawling out of the field. Dazed and wounded horses hobbled about without direction. From beasts and riders too injured to move came a torpid chorus of groans and wails, and nearly two hundred enemy warriors did not move at all. Still, Batu estimated the invaders' casualties at under five hundred, less than two-thirds of his own. His men had not even given as good as they'd received.

"Your archers have been too devastating," Kwan continued, ignoring the scrying basin. "Send a runner. This time, your archers must let the barbarians complete the charge."

Batu's jaw dropped, for the minister was wasting what remained of his limited supply of archers. "Perhaps the minister's eyes are not as sharp as they once were," Batu said, barely able to keep his voice from trembling with anger. "Or he would have noticed that my archers did not stop the last charge, and could not stop the next one if the enemy walked their horses into battle!"

Kwan's response was measured and cool. "My eyes are sharp enough to know when we have the enemy in our grasp. Your pengs are a tribute to your discipline," the minister said. The term he used could mean weapon, common soldier, or both, reflecting the opinion that soldiers were weapons. "They deserve the empire's praise," Kwan added. "But if we send reinforcements now, my young general, the barbarians will smell our trap and flee. Without horses, we'll never catch them."

"The enemy's nose is sharper than you think," Batu retorted. "He has already smelled the trap, and he is stealing the bait while we watch." Batu looked at his fellow generals. "If the horsewarriors are such fools, wouldn't they have committed themselves by now?"

Neither general answered. They were unwilling to contradict the logic of their young peer, yet unwilling to support him. The Minister of War disagreed with Batu, and the older generals knew it would not be prudent to contradict their superior. As the two men looked away, Batu recognized their caution and realized that he could expect no help from them. He wondered if they would prove as unsupportive on the battlefield.

For a moment, the minister regarded Shengti and Ching Tung thoughtfully. Finally, turning back to Batu, he said, "It is possible that you are correct, General. If there is not enough bait, the rat may smell the trap. So we will increase his temptation."

The concession surprised Batu, and he wondered if it should have. Although it was apparent that the minister lacked battlefield experience, it was equally obvious that only a shrewd politician could have reached such a high post. It seemed to the young general that Kwan had interpreted Shengti's and Ching Tung's silence for what it was. Batu allowed himself the vague hope that Kwan's supervision would not result in a disaster after all.

While the young general considered him, Kwan studied the scrying basin. Finally, the old man poin

ted a yellow-nailed finger to where the end of the archer's line met the river. "General Batu, take your army and reinforce your archers," the minister said. "Anchor your line here, at the river, and deploy as if expecting a frontal attack. Leave your western flank exposed."

A knot of anger formed in Batu's heart. He openly frowned at the minister, hardly able to believe what he had heard. "If I do that, the barbarian cavalry will ride down the line and drive my army into the river."

"Exactly," Kwan said, pulling his gray lips into a thin smile.

Shengti studied the scrying basin for a moment, then said, "A brilliant plan, Minister! The sloppy deployment will lure the enemy into full commitment. As the barbarians roll up Batu's flank, my army-along with the Army of Ching Tung, of course-will charge over the hill and smash them."

The ancient minister smiled warmly at Shengti. "You are very astute," he said. "Your future will have many bright days."

And my future will be very short, Batu thought. Shengti had neglected to mention the most clever part of Kwan's plan: a troublesome subordinate would be destroyed. Even if Batu did not perish during the slaughter, the stigma of losing an entire army would destroy his career.

Still, even knowing the consequences, Batu's instinct was to follow the order without question. To his way of thinking, soldiers were dead men. Their commanders simply allowed them to walk the land of the living until their bodies were needed in combat. In that respect, Batu considered himself no different from any other soldier, and if Kwan ordered him to meet the enemy naked and alone, he would be obliged to do so.

Still, a soldier was entitled to the hope of a glorious end. The young general could see no glory in allowing the horse-warriors to slaughter his army like so many swine, especially when Kwan had not taken the time to scout the enemy and could not be certain that anything useful would come of the sacrifice. Hoping to convince the generals from Shengti and Ching Tung to come to his aid, Batu decided to point out Kwan's sloppy preparations.

Shadows of Reach: A Master Chief Story

Shadows of Reach: A Master Chief Story Pages of Pain p-1

Pages of Pain p-1 Star Wars 396 - The Dark Nest Trilogy III - The Swarm War

Star Wars 396 - The Dark Nest Trilogy III - The Swarm War Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Apocalypse

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Apocalypse A Forest Apart

A Forest Apart Star Wars: Dark Nest II: The Unseen Queen

Star Wars: Dark Nest II: The Unseen Queen Star Wars: A Forest Apart

Star Wars: A Forest Apart Tempest: Star Wars (Legacy of the Force) (Star Wars: Legacy of the Force)

Tempest: Star Wars (Legacy of the Force) (Star Wars: Legacy of the Force) Star by Star

Star by Star Crucible: Star Wars

Crucible: Star Wars Last Light

Last Light Invincible

Invincible Inferno

Inferno Star Wars - The Trouble With Squibs

Star Wars - The Trouble With Squibs Abyss

Abyss The Verdent Passage

The Verdent Passage Vortex: Star Wars (Fate of the Jedi) (Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi)

Vortex: Star Wars (Fate of the Jedi) (Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi) Dragonwall e-2

Dragonwall e-2 The Amber Enchantress

The Amber Enchantress Crucible

Crucible The Titan of Twilight

The Titan of Twilight Dragonwall

Dragonwall Beyond the High Road c-2

Beyond the High Road c-2 The Siege rota-2

The Siege rota-2 Silent Storm: A Master Chief Story

Silent Storm: A Master Chief Story The Ogre's Pact

The Ogre's Pact The Sorcerer rota-3

The Sorcerer rota-3 The Parched sea h-1

The Parched sea h-1 The Giant Among Us

The Giant Among Us Recovery

Recovery Star Wars: Dark Nest 1: The Joiner King

Star Wars: Dark Nest 1: The Joiner King Faces of Deception le-2

Faces of Deception le-2 The Parched Sea

The Parched Sea The Ogre's Pact зк-1

The Ogre's Pact зк-1 Apocalypse

Apocalypse Star Wars®: Dark Nest I: The Joiner King

Star Wars®: Dark Nest I: The Joiner King The Titan of Twilight ttg-3

The Titan of Twilight ttg-3 The Giant Among Us ttg-2

The Giant Among Us ttg-2 The Summoning rota-1

The Summoning rota-1 Tatooine Ghost

Tatooine Ghost Star Wars®: Dark Nest III: The Swarm War

Star Wars®: Dark Nest III: The Swarm War Retribution

Retribution A Forest Apart: Star Wars (Short Story)

A Forest Apart: Star Wars (Short Story) Faces of Deception

Faces of Deception The Veiled Dragon h-12

The Veiled Dragon h-12 Star Wars 390 - The Dark Nest Trilogy I - The Joiner King

Star Wars 390 - The Dark Nest Trilogy I - The Joiner King Waterdeep

Waterdeep STAR WARS: NEW JEDI ORDER: RECOVERY

STAR WARS: NEW JEDI ORDER: RECOVERY